“The Devil-Doll” (1936) Falsely convicted for murder and embezzlement by his former partners, Lionel Barrymore escapes prison on Devil’s Island and seizes upon a bizarre plan for revenge: using technology developed by dotty scientist and fellow convict Henry B. Walthal, whose solution to world hunger is to shrink everyone down to doll size (smaller mouths eat less food, you see), Barrymore reduces a maid (Grace Ford) and one of his partners (Paul Foltz) to doll size and sends them out to wreak havoc on his former associates. Final horror film from Tod Browning (“Freaks,” “Dracula”) is unquestionably absurd, and made all the more so by Barrymore disguising himself as a female doll maker (shades of Lon Chaney in Browning’s “The Unholy Three,” as the film’s trailer points out) to carry out his scheme, which, we learn, intended to make sure daughter (Maureen O’Sullivan) will receive his inheritance. But what might have played as lunatic camp for any other filmmaker is made not only palatable but also unsettling by Browning’s penchant for weird imagery, like a tiny Foltz, tricked out as an Apache dancer, stalking his victim by a Christmas tree. The presence of Barrymore as the quasi-sympathetic anti-hero is a plus (even in his unconvincing drag costume), as are the impressive (for the period) special effects and Rafaello Ottiano, who’s a major assist in maintaining the horror mood as Walthal’s crazed wife, for whom miniaturizing has become an unhealthy obsession. “The Devil-Doll,” and all of the films reviewed in this column, is included in Warner Archives Collection’s three-disc reissue of its fine “Hollywood Legends of Horror” set.

“The Devil-Doll” (1936) Falsely convicted for murder and embezzlement by his former partners, Lionel Barrymore escapes prison on Devil’s Island and seizes upon a bizarre plan for revenge: using technology developed by dotty scientist and fellow convict Henry B. Walthal, whose solution to world hunger is to shrink everyone down to doll size (smaller mouths eat less food, you see), Barrymore reduces a maid (Grace Ford) and one of his partners (Paul Foltz) to doll size and sends them out to wreak havoc on his former associates. Final horror film from Tod Browning (“Freaks,” “Dracula”) is unquestionably absurd, and made all the more so by Barrymore disguising himself as a female doll maker (shades of Lon Chaney in Browning’s “The Unholy Three,” as the film’s trailer points out) to carry out his scheme, which, we learn, intended to make sure daughter (Maureen O’Sullivan) will receive his inheritance. But what might have played as lunatic camp for any other filmmaker is made not only palatable but also unsettling by Browning’s penchant for weird imagery, like a tiny Foltz, tricked out as an Apache dancer, stalking his victim by a Christmas tree. The presence of Barrymore as the quasi-sympathetic anti-hero is a plus (even in his unconvincing drag costume), as are the impressive (for the period) special effects and Rafaello Ottiano, who’s a major assist in maintaining the horror mood as Walthal’s crazed wife, for whom miniaturizing has become an unhealthy obsession. “The Devil-Doll,” and all of the films reviewed in this column, is included in Warner Archives Collection’s three-disc reissue of its fine “Hollywood Legends of Horror” set.

“Mark of the Vampire” (1935) Are vampires to blame for the death of a Czech baron, found dead in his mansion and drained of blood? Sightings of a mysterious count (Bela Lugosi) and his spectral daughter (Carroll Borland) on the grounds of the estate certainly point to that notion, but police inspector Lionel Atwill and occult expert Lionel Barrymore aren’t so sure. Tod Browning’s talkie remake of his famously lost “London at Midnght” (1927) is long on Gothic atmosphere courtesy of cinematographer James Wong Howe, which along with the presence of (a mostly and disappointingly silent) Lugosi and the Morticia/Vampira-esque Borland, are the most satisfying elements of the film. Less so is the denouement, which hangs on one of the more irritating horror tropes; commentary by Kim Newman and Steve Jones (enjoyable and informative, as always) illustrates fans’ aggravation with the film’s inability (or refusal) to live up to the promise of its first act. The original trailer, which features Lugosi (speaking more lines than he does in the film), is included.

“Mark of the Vampire” (1935) Are vampires to blame for the death of a Czech baron, found dead in his mansion and drained of blood? Sightings of a mysterious count (Bela Lugosi) and his spectral daughter (Carroll Borland) on the grounds of the estate certainly point to that notion, but police inspector Lionel Atwill and occult expert Lionel Barrymore aren’t so sure. Tod Browning’s talkie remake of his famously lost “London at Midnght” (1927) is long on Gothic atmosphere courtesy of cinematographer James Wong Howe, which along with the presence of (a mostly and disappointingly silent) Lugosi and the Morticia/Vampira-esque Borland, are the most satisfying elements of the film. Less so is the denouement, which hangs on one of the more irritating horror tropes; commentary by Kim Newman and Steve Jones (enjoyable and informative, as always) illustrates fans’ aggravation with the film’s inability (or refusal) to live up to the promise of its first act. The original trailer, which features Lugosi (speaking more lines than he does in the film), is included.

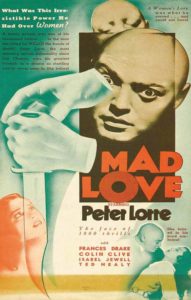

“Mad Love” (1935) In his American film debut, Peter Lorre fuels the deranged passions running beneath this thriller, directed by Oscar-winning cinematographer Karl Freund (“Dracula”) and based on Maurice Renard’s amputation/possession horror “The Hands of Orlac.” With his bald, gleaming skull and staring eyes, Lorre is the center of attention throughout the film as Dr. Gogol, a brilliant surgeon obsessed with actress Frances Drake. Drake rebuffs Lorre’s romantic overtures, but turns to him in desperation after her pianist husband (Colin Clive of “Frankenstein”) loses the use of his hands in a train accident. Lorre provides Clive with a new set of hands, which work perfectly well, with one new feature: having been removed from a blade-wielding killer, Clive has developed a talent for throwing knives (Edward Brophy), and, it appears, an appetite for murder. Freund gives the picture some startling imagery – right from the star, with disembodied hands crashing through the main titles – but the picture is a showcase for Lorre’s intense energy and ability to not plumb the depths of dark psychology but find sympathy and humanity within them; he is convincing mooning over Drake, who is threatened nightly as the victim in a Grand Guignol performance, as he is lurking behind dark glasses and a metallic exo-skeleton, giggling madly as he pretends to be the dead Brophy, come back to life to drive Clive mad. Lorre is the reason to see the picture, without question, though WAC’s clean print – a vast improvement over battered TV versions – is a highlight; Steve Haberman discusses the source material, which was made several times into various features (including “The Hands of Orlac,” with Christopher Lee, and “Hands of a Stranger”)

“Mad Love” (1935) In his American film debut, Peter Lorre fuels the deranged passions running beneath this thriller, directed by Oscar-winning cinematographer Karl Freund (“Dracula”) and based on Maurice Renard’s amputation/possession horror “The Hands of Orlac.” With his bald, gleaming skull and staring eyes, Lorre is the center of attention throughout the film as Dr. Gogol, a brilliant surgeon obsessed with actress Frances Drake. Drake rebuffs Lorre’s romantic overtures, but turns to him in desperation after her pianist husband (Colin Clive of “Frankenstein”) loses the use of his hands in a train accident. Lorre provides Clive with a new set of hands, which work perfectly well, with one new feature: having been removed from a blade-wielding killer, Clive has developed a talent for throwing knives (Edward Brophy), and, it appears, an appetite for murder. Freund gives the picture some startling imagery – right from the star, with disembodied hands crashing through the main titles – but the picture is a showcase for Lorre’s intense energy and ability to not plumb the depths of dark psychology but find sympathy and humanity within them; he is convincing mooning over Drake, who is threatened nightly as the victim in a Grand Guignol performance, as he is lurking behind dark glasses and a metallic exo-skeleton, giggling madly as he pretends to be the dead Brophy, come back to life to drive Clive mad. Lorre is the reason to see the picture, without question, though WAC’s clean print – a vast improvement over battered TV versions – is a highlight; Steve Haberman discusses the source material, which was made several times into various features (including “The Hands of Orlac,” with Christopher Lee, and “Hands of a Stranger”)

“Doctor X” (1932) Should anyone tell you that black-and-white horror films are dull, or worse, not scary, please point them to this medical horror film by Michael Curtiz (“Casablanca”), which folds cannibalism, serial murder, deranged science experiments, artificial flesh and unseemly obsessions into its 76-minute running time. Yes, you have to slog through comic relief hero Lee Tracy’s mugging (enough with the joy buzzer, already) and mooning over Fay Wray, but the picture’s high/weird points – suspicious medico Lionel Atwill’s experiment to determine which of the oddball scientists in his employ is the flesh-eating Full Moon Killer, which involves strapping them into an electronic device and re-enacting the murders to record their reactions (!), and the gruesome closer, in which the Killer reveals his hideous disguise (created by Max Factor) and even more appalling reason for the crimes – are as jaw-dropping for modern audiences as they were for moviegoers eight decades ago. The WAC disc presents “Doctor X” in its 2-strip Technicolor format (a B&W version was filmed at the same time), which heightens the surreal quality of the proceedings; Scott MacQueen’s commentary addresses the film’s origin as a stage play and other production and cast details (Curtiz, Atwill and Wray reunited the following year for another memorable 2-strip Technicolor thriller, “Mystery of the Wax Museum”).

“Doctor X” (1932) Should anyone tell you that black-and-white horror films are dull, or worse, not scary, please point them to this medical horror film by Michael Curtiz (“Casablanca”), which folds cannibalism, serial murder, deranged science experiments, artificial flesh and unseemly obsessions into its 76-minute running time. Yes, you have to slog through comic relief hero Lee Tracy’s mugging (enough with the joy buzzer, already) and mooning over Fay Wray, but the picture’s high/weird points – suspicious medico Lionel Atwill’s experiment to determine which of the oddball scientists in his employ is the flesh-eating Full Moon Killer, which involves strapping them into an electronic device and re-enacting the murders to record their reactions (!), and the gruesome closer, in which the Killer reveals his hideous disguise (created by Max Factor) and even more appalling reason for the crimes – are as jaw-dropping for modern audiences as they were for moviegoers eight decades ago. The WAC disc presents “Doctor X” in its 2-strip Technicolor format (a B&W version was filmed at the same time), which heightens the surreal quality of the proceedings; Scott MacQueen’s commentary addresses the film’s origin as a stage play and other production and cast details (Curtiz, Atwill and Wray reunited the following year for another memorable 2-strip Technicolor thriller, “Mystery of the Wax Museum”).

“Return of Dr. X” (1939) In-name-only follow-up to “Doctor X” follows newspaper hound Wayne Morris and internist Dennis Morgan’s investigation into a series of murders in which the victims are found drained of their rare blood type; their amateur sleuthing brings them to Morgan’s former teacher, hematologist John Litel, whose sepulchral assistant (Humphrey Bogart), bears a strong resemblance to the very dangerous – and very dead – killer, Dr. Maurice Xavier. Modest B-thriller is best remembered for the unlikely casting of Bogart (in a role intended for Karloff or Lugosi) as a sort of vampire; though he’s given a terrific look – pale face and jet-black hair shot through with a “Bride of Frankenstein” streak – the actor is an awkward fit and lends little to actor-turned-director Vincent Sherman’s attempts to maintain an atmosphere of suspense or horror (Bogart also loathed the role, one of seven he played in 1939 alone, and reportedly refused to discuss it). Probably best enjoyed for the camp/cult value or for B&W horror devotees; Sherman, who went on to enjoy a career helming A-list studio pictures like “Mr. Skeffington” and “Nora Prentiss,” joined Steve Haberman on the commentary track, which provides a wealth of info on the production and Bogart.

“Return of Dr. X” (1939) In-name-only follow-up to “Doctor X” follows newspaper hound Wayne Morris and internist Dennis Morgan’s investigation into a series of murders in which the victims are found drained of their rare blood type; their amateur sleuthing brings them to Morgan’s former teacher, hematologist John Litel, whose sepulchral assistant (Humphrey Bogart), bears a strong resemblance to the very dangerous – and very dead – killer, Dr. Maurice Xavier. Modest B-thriller is best remembered for the unlikely casting of Bogart (in a role intended for Karloff or Lugosi) as a sort of vampire; though he’s given a terrific look – pale face and jet-black hair shot through with a “Bride of Frankenstein” streak – the actor is an awkward fit and lends little to actor-turned-director Vincent Sherman’s attempts to maintain an atmosphere of suspense or horror (Bogart also loathed the role, one of seven he played in 1939 alone, and reportedly refused to discuss it). Probably best enjoyed for the camp/cult value or for B&W horror devotees; Sherman, who went on to enjoy a career helming A-list studio pictures like “Mr. Skeffington” and “Nora Prentiss,” joined Steve Haberman on the commentary track, which provides a wealth of info on the production and Bogart.

“The Mask of Fu Manchu” (1932) Scotland Yard’s Nayland Smith (Lewis Stone) and a team of British archaeologists race against time to retrieve artifacts, allegedly owned by Genghis Khan and possessed of tremendous power, before the megalomaniacal Fu Manchu (Boris Karloff) can use them in his plan to exterminate the white race! Time and changing cultural attitudes have largely invalidated the pulpy pleasures of this MGM production, which underscore the uglier side of the “Yellow Peril” myth (a virulent notion sold wholesale by co-producer William Randolph Hearst through his newspaper empire) and yellowface casting; it’s too bad, as both Karloff and Myrna Loy, as his equally fiendish and overheated daughter Fah Lo See, give arch, dastardly performances, and art director Cedric Gibbons’ berserk designs for Fu’s palace – a berserk amalgam of European severity and faux-Asian splendor – are also worth a look. Director Charles Brabin (who was married to vamp icon Theda Bara) pays homage to Sax Rohmer’s source material by favoring pace over script logic, and devotes considerable time to Fu’s array of torture devices – crocodile pits, endless tolling bells, crushing walls with spikes – and a lunatic conclusion that sees Stone obliterating Fu’s henchman with a death ray (created by Kenneth Strickfaden, who also outfitted Colin Clive’s lab in “Frankenstein”). Commentary by historian Gregory Mank discusses Asian response to the film (not positive) and details censorial edits – Fu spewing racial hatred – which have been restored to this print.

“The Mask of Fu Manchu” (1932) Scotland Yard’s Nayland Smith (Lewis Stone) and a team of British archaeologists race against time to retrieve artifacts, allegedly owned by Genghis Khan and possessed of tremendous power, before the megalomaniacal Fu Manchu (Boris Karloff) can use them in his plan to exterminate the white race! Time and changing cultural attitudes have largely invalidated the pulpy pleasures of this MGM production, which underscore the uglier side of the “Yellow Peril” myth (a virulent notion sold wholesale by co-producer William Randolph Hearst through his newspaper empire) and yellowface casting; it’s too bad, as both Karloff and Myrna Loy, as his equally fiendish and overheated daughter Fah Lo See, give arch, dastardly performances, and art director Cedric Gibbons’ berserk designs for Fu’s palace – a berserk amalgam of European severity and faux-Asian splendor – are also worth a look. Director Charles Brabin (who was married to vamp icon Theda Bara) pays homage to Sax Rohmer’s source material by favoring pace over script logic, and devotes considerable time to Fu’s array of torture devices – crocodile pits, endless tolling bells, crushing walls with spikes – and a lunatic conclusion that sees Stone obliterating Fu’s henchman with a death ray (created by Kenneth Strickfaden, who also outfitted Colin Clive’s lab in “Frankenstein”). Commentary by historian Gregory Mank discusses Asian response to the film (not positive) and details censorial edits – Fu spewing racial hatred – which have been restored to this print.

I always really enjoy these posts!

Thank you very much!